How to Establish Tone

And how to build a tiny door into your audience's mind. Breaking down "Being John Malkovich".

What’s “tone”? Level of reality? Genre? Both?

Imagine trying to explain what the tone of Being John Malkovich was when Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman got their cult project going. Hard to put into words, but the feeling is very specific, isn’t it?

And since we can’t get into Charlie and Spike’s heads (door or no door), let’s look at their creation and break down how they establish the tone and make us care about Craig.

Because if you can sell the audience an idea about a tiny door into someone’s head, you can sell them anything (and that’s what we’re after, right?).

Let's take a look at the opening sequence

A grand opening, audience applauds, epic music fills the space, and the curtain slides open on a new puppet show. It’s talented, it’s raw, it’s about some deep yearning, a lack of something - we don’t yet know what. The puppet and the puppeteer become one. Audience erupts - and we reveal Craig is actually alone, practicing in his garage.

The next morning starts with the parrot waking Craig up. He stays in bed, while his girlfriend Lotte suggests he get a job, until the puppetry takes off. They had this talk before.

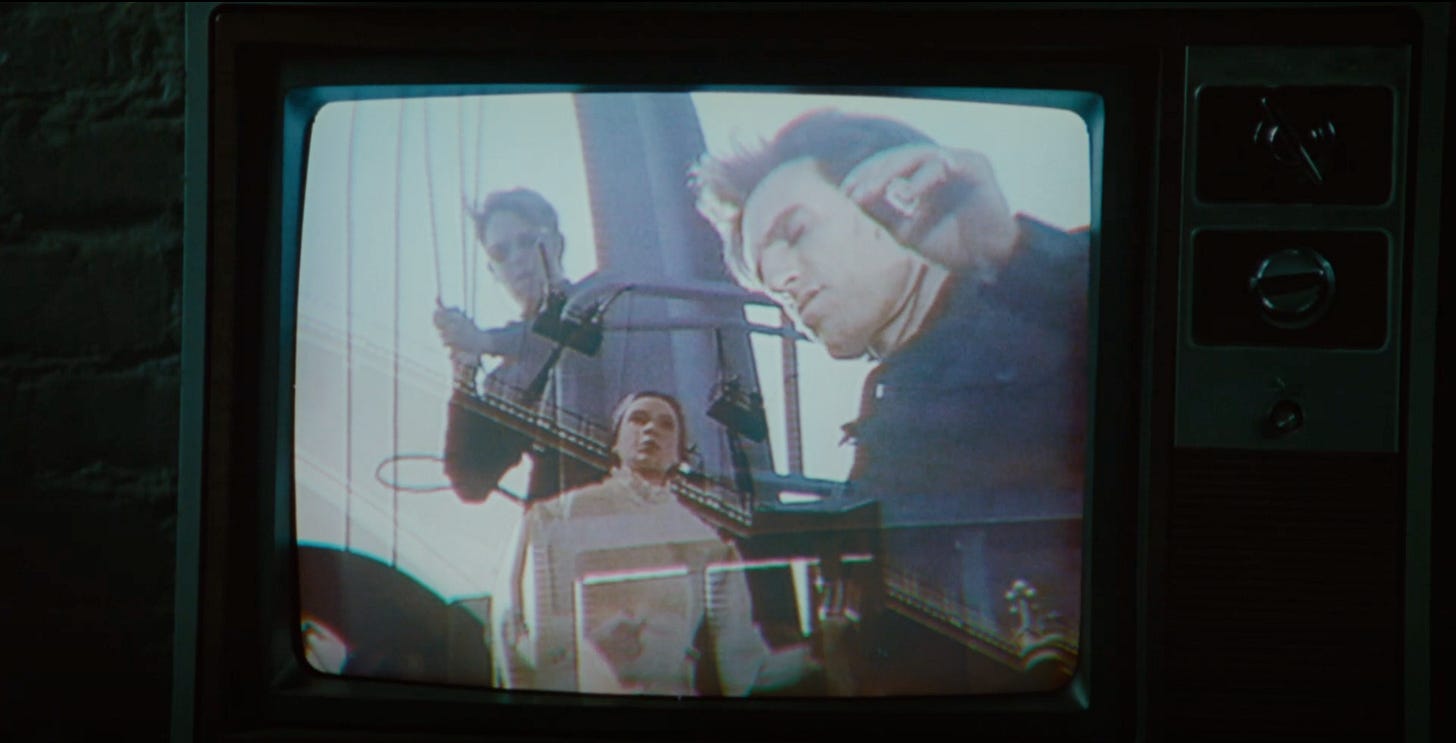

Lotte’s out, and Craig is watching TV, sitting on the couch next to a chimp Lotte’s fostering. On screen, rival star puppeteer and “a gimmicky bastard,” as Craig calls him, feeling sorry for himself, bouncing the pain of human existence off the chimp.

Cut. And we’re on the street where Craig’s putting up one of his performances for passersbys. A play of sexual desire and longing for something real grabs the attention of an unsuspecting little girl, much to her father’s anger, who punches Craig in the face.

End sequence.

If I told you that in about 20 minutes, Craig will find a tiny door leading into the head of a known actor, John Malkovich, literally… would you buy it? Or would that be too bizarre? Well, we know the answer. But why does it work? And how the hell do you sell the audience an idea like that?

Why It Works Psychologically

1. Expectation Violation

And no, it’s not about a bad one-night stand

The drastic switch from a grand, triumphant puppet stage to Craig’s dreary reality is a prime example of how contrast can make us pay attention. We instinctively perk up at this expectation violation – it stands out from the ordinary, triggering a surge of interest (even a tiny dopamine reward) in our brain’s reward centers. So, surprise feels good - physically.

By giving us a window (tiny door, wink-wink) into Craig’s aspirations of an artistic dream and then grounding us with his failure and loneliness engages us. We’re now actively wondering about the gap between his inner talent and his outer life – a curiosity hook that pulls us into the story.

2. Inequity Aversion

Craig is a skilled puppeteer with big dreams (that’s “competence attracts” btw, I talked about in my previous breakdown), yet the world gives him nothing but a literal punch in the face. This disparity sparks our innate sense of injustice. Psychologists call it inequity aversion. We’ve evolved to feel moral outrage at unfair situations because “fairness” is crucial for cooperative societies.

In storytelling, that means when we see a character treated unfairly despite their competence, we immediately empathize. Our brains literally light up with anger and disgust when we witness what we perceive as injustice. So instead of shrugging at Craig’s woes, we rally to his side. We feel the “that’s not right!” emotion, which bonds us to him and makes us invested in seeing things set right.

3. Novelty & Absurdity

A parrot instead of an alarm clock? A pet chimpanzee with PTSD? These bizarre touches in an otherwise normal domestic scene create a tone of playful absurdity that actually heightens our engagement. Why? Our brains love novelty. Unusual, out-of-place elements grab attention and piqué curiosity – they act like brain candy, activating our interest and focus. Instead of tuning out banal exposition (“get a job, Mikhail Craig…”), we’re alert, trying to make sense of the oddities. This curiosity gap keeps us from questioning the story’s plausibility; we willingly go along, intrigued by the weirdness.

Psychologically, throwing a few absurd bits at an audience is like a primer for suspension of disbelief – it signals that this world operates on quirky logic, so we adapt our expectations. By the time an outright fantastical device (a portal into John Malkovich’s head) arrives, we’re already conditioned to accept it. In essence, the small absurdities not only entertain us but also lower our skepticism. We stay open-minded and engaged because the story has proven it can surprise and delight us in creative ways (and our brains are on the lookout for the next twist).

Uh… so what do I do?

Alternative title: How many shrooms do I need to do to come up with a tiny door into someone’s head? Write your answers in the comments 😉

1. Want to surprise the audience?

Build a line of expectation, and catch the audience when they don’t expect it. Use two clues and subversion.

First clue - grand opening, audience applauds, curtain slides open. What is the viewer thinking? It looks like a big play, right? Maybe…

Check.

Then, skillful puppeteer, raw, emotional performance - audience erupts. (The viewer is now certain they’re watching a grand play).

We got them. Time to use subversion.

It’s not a grand opening. It’s Craig in his garage. Lonely, unsettled, chugging beer.

What to do:

Give the audience two clues that direct their thinking, and then subvert it. Two clues establish a pattern, and if it’s clear enough, you will direct the audience into thinking what you want them to think. Then hit them with subversion - boom! You can almost hear their dopamine firing.

2. Want to get the audience morally outraged?

Post some racist or sexist tweets.

Comment on Israel/Palestine/Pakistan/India/Ukraine/Russia.

Say there’s no Epstein list. (Too far?)

2a. Want to get the audience morally outraged using dramaturgy?

Craig’s got talent, he’s got passion for his craft. He’s dedicated. All he needs is a chance. Instead, that “gimmicky bastard” Derek Mantini sets up a show with giant puppets, while Craig has to babysit a chimp and get punched in the face.

What to do:

Make your character fight for their goals, show passion, act with competence, but put them in “unfair”, “disadvantageous” circumstances. As long as you convey that the disadvantage is out of the character’s hands, but the result of society/government/the other audience will feel it. It’s primal.

3. Want to get a complex tone across?

The proof device is what you are looking for. It’s your go-to tool for creating any sort of patterns, whether you’re establishing tone, theme, genre, or even certain aspects of characters’ personalities.

Want to cook it up? Present the audience with a thesis and argumentation of a specific element. We see it being used to establish tone in the opening sequence:

Thesis (first element): Parrot wakes Craig up, and Craig doesn’t react to it. It’s a mundane thing for him. The thesis suggests that in Craig’s routine, the parrot acting as a sort of alarm clock is normal. For us, it’s a bit absurd, but hey, whatever rocks your boat. There’s no pattern here yet.

Argumentation (second element): Craig is watching TV on the couch next to a chimp, having a profound (albeit one-sided) conversation about the human condition. Absurd? Yeah.

Now we have two dots to connect. Actually, our minds already did, even without us noticing. If in this world, the parrot can be a part of everyday morning routine, and having existential crisis next to a chimp is absolutely normal, then other absurdist elements are nothing of the ordinary… and there will be a lot of them later.

What to do:

Use a proof device to create patterns for the audience to latch onto, whether it’s to establish tone, genre, character, etc. Create a situation emphasizing the element you want to “prove”, then repeat that element in a slightly different context. That will create a pattern in the audience’s mind that they’ll accept as a constant or a baseline of your story and will not question it later.

So, what is tone? It’s certain patterns your story establishes and adheres to.

Whenever you break out of that framework you created in the audience’s mind, the tone becomes inconsistent.

So the more aware you are about the patterns you create, consciously or not, the faster you can sell your script and become famous the better experience you can create for the audience.

Ok. Now the important stuff. Below is the kitty photo. You’re welcome to scroll down, but only if you hit this button:

Don’t scroll down unless you subscribed.

Did you subscribe?

Did you really?

If you didn’t, I’ll find you.

Just kidding. If you got so far, you deserve the kitty picture. Also, why not share the post if you enjoyed it?

See you next Tuesday.